2 Making Education Accessible to All Students

IDEA: Equitable Access to Education for All Children

Tanessa Sanchez and Kerry Diaz

Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter, you should be able to:

- Understand the history and impact of the Individual with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).

- Compare accommodations and modification in instruction to meet individual student needs.

- Describe Response to Intervention (RTI) and its benefits.

- Identify the roles and responsibilities of those who work in making education accessible.

- Compare and contrast the key principles of language-first vs. identify-first language.

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) highlights the importance of equitable access to education for all children, particularly those with disabilities. Initially enacted in 1975 and reauthorized several times, IDEA mandates that public schools provide free and appropriate public education (FAPE) in the least restrictive environment (LRE) possible. This ensures that children with disabilities can access the general education curriculum alongside their peers with necessary support (U.S. Department of Education, 2020).

IDEA emphasizes the development of individualized education programs (IEPs) that outline specific goals, accommodations, and modifications tailored to each child’s unique needs. This individualized approach aligns with Gardner’s theory, recognizing that each child has different intelligences and learning styles.

History of IDEA

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) is a landmark law that guarantees a free and appropriate public education (FAPE) to children with disabilities in the United States. Its evolution reflects growing recognition of the rights of individuals with disabilities and the need to ensure they receive equal access to education.

Early Advocacy and Predecessors (Before 1970s)

Before the 1970s, children with disabilities were often excluded from public schools or segregated into special institutions. There was limited legal protection for their right to receive an education, and many children with disabilities were denied access to schools altogether.

- 1940s-1950s: The disability rights movement began to emerge during and after World War II, with advocates pushing for better services for people with disabilities. Many disabilities advocates fought to ensure that children with disabilities were included in educational settings.

- 1960s-1970s: The Civil Rights Movement and the push for social justice also extended to the disability community. Families and advocates began organizing to challenge the exclusion of children with disabilities from public education.

The Early Legislation (1970s)

The Education of All Handicapped Children Act (EAHCA): The first major federal law aimed at securing the rights of students with disabilities was passed in 1975 under President Gerald Ford. The Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EAHCA) required states to provide children with disabilities access to a free, appropriate public education. The law mandated:

- Free and Appropriate Public Education (FAPE): Children with disabilities had the right to a free education that met their individual needs.

- Least Restrictive Environment (LRE): Students with disabilities were to be educated alongside their non-disabled peers to the maximum extent possible.

- Individualized Education Programs (IEPs): Each student with a disability had to have an IEP that was tailored to their unique educational needs.

The EAHCA marked a monumental shift, recognizing that all children, regardless of disability, should have access to public education.

Revisions and Name Change (1980s – 1990s)

- 1986 – Amendments to EAHCA: The law was amended to include early intervention services for infants and toddlers with disabilities. These services were designed to support children from birth to age three, further expanding the reach of special education.

- 1990 – The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA): The EAHCA was renamed to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. This amendment included the following significant provisions:

- Inclusion of Autism and Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) as specific disabilities eligible for special education services.

- Transition Services: The law required schools to begin preparing students with disabilities for life after high school, including vocational training and other services that would help them transition to adulthood.

- 1997 – IDEA Amendments: Further updates to IDEA were made in 1997, which emphasized:

- Accountability: Schools were required to show that students with disabilities were making progress.

- Increased Parent Involvement: Parents were given more rights to be involved in their child’s educational planning and decision-making.

- Behavioral Plans: Schools were required to implement behavioral assessments and intervention plans for students whose disabilities affected their behavior.

Further Revisions and Enhancements (2000s – Present)

- 2004 – IDEA Reauthorization: The law was reauthorized again in 2004, with several key changes, including:

- Alignment with No Child Left Behind (NCLB): The law’s emphasis on standardized testing and accountability was integrated into IDEA. Schools were expected to show that students with disabilities were meeting academic standards.

- Response to Intervention (RTI): The reauthorization provided for the use of RTI, a process that helps identify students who are struggling early on and provide interventions before they are formally classified as having disabilities.

- Greater Flexibility for States: States were allowed more flexibility in implementing IDEA requirements, but they were still required to meet federal standards and maintain accountability.

- 2006 – Regulations for IDEA: The U.S. Department of Education issued new regulations to clarify how IDEA should be implemented. These regulations addressed issues such as the definition of “special education,” the process for determining eligibility, and procedures for due process hearings.

- 2015 – Significant Shift in Educational Practices: There was a continued push to improve inclusive practices and ensure that students with disabilities have meaningful access to academic content in general education classrooms, including the use of technology to support learning.

- 2020s – Modern Updates: Continued refinements have been made to IDEA, with increased attention on ensuring access to digital learning and addressing new challenges related to mental health and disabilities.

Key Principles and Achievements of IDEA

Since its inception, IDEA has led to significant progress in the education of children with disabilities. Some of the key principles include:

- Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE): Ensuring that all children, regardless of disability, have access to free and quality public education.

- Least Restrictive Environment (LRE): Students with disabilities should be educated in the least restrictive environment possible, ideally alongside their non-disabled peers.

- Individualized Education Programs (IEPs): Every student with a disability must have an IEP, tailored to their specific needs and goals.

- Parent and Student Participation: IDEA has consistently emphasized the importance of involving parents in the educational process and planning for students with disabilities.

- Focus on Accountability: Schools and educators are held accountable for ensuring that students with disabilities receive meaningful educational opportunities and achieve positive outcomes.

Impact and Challenges

IDEA has been transformative in providing educational opportunities to millions of children with disabilities. However, challenges remain, including:

- Ensuring full and effective implementation of IDEA in all schools, particularly in underfunded districts.

- Addressing disparities in outcomes for students with disabilities, especially in minority communities.

- Continuing to adapt IDEA to the evolving educational needs, including the integration of technology and mental health services.

Key Points of the Least Restrictive Environment (LRE):

The Least Restrictive Environment (LRE) is a fundamental principle of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). It ensures that students with disabilities receive an education alongside their non-disabled peers to the greatest extent possible. LRE promotes inclusion, socialization, and access to the general curriculum while recognizing that some students may require specialized settings and support services.

Inclusion in General Education

LRE emphasizes that students with disabilities should spend as much time as possible in general education classrooms. This approach fosters both academic and social development by allowing students to learn and interact with their peers in a diverse and inclusive environment.

Continuum of Placements

While full inclusion is ideal, LRE recognizes that not all students can succeed in general education without additional support. IDEA provides a continuum of alternative placements to meet individual needs, including:

- Full Inclusion: The least restrictive setting where the student is fully integrated into general education with supports, often with modifications to the curriculum or teaching strategies.

- Part-Time Inclusion: Students with disabilities might spend part of their day in a general education classroom and part of the day in a special education classroom or with additional support.

- Separate Classes or Schools: For students with more severe disabilities who cannot succeed in general education settings, a more restrictive environment may be appropriate. However, this is seen as a last resort, only after considering all possible alternatives in the least restrictive setting.

Supports and Services

LRE is not just about where a student is placed—it also includes providing necessary supports to help them succeed, such as:

- Special education services (e.g., speech therapy, occupational therapy).

- Accommodations and modifications (e.g., extra time on tests, assistive technology).

- Classroom aides or paraprofessionals for academic and behavioral assistance.

Decision-Making Process

A student’s placement is determined by their Individualized Education Program (IEP) team, which includes parents, teachers, and specialists. The team assesses the child’s needs and balances specialized services with opportunities for inclusion.

Maximizing Inclusion

A student should only be placed in a more restrictive setting if:

- Their disability significantly limits their ability to progress in general education, even with support.

- Their behavior or educational needs require a specialized environment to ensure effective learning.

Social and Academic Benefits

Research has shown that inclusive education benefits students with disabilities by improving academic performance, social skills, and self-confidence. Additionally, it fosters empathy, understanding, and acceptance among all students, creating a more inclusive school community.

Conclusion

The LRE mandate is designed to prevent the unnecessary segregation of students with disabilities, ensuring they are not excluded from educational opportunities due to their disabilities. Schools must demonstrate that they are making reasonable efforts to include students with disabilities in general education settings and that the benefits of inclusion are maximized while still meeting each child’s individual educational needs. By balancing appropriate placements with necessary supports, LRE promotes equal access to education and fosters an inclusive learning environment for all students.

Apply

Read the following anecdote and answer the questions.

- Why do you think the parents, teachers and school deem the general education classroom the least restrictive environment for Ethan?

- What did the parents, teachers and school do to make the general education environment accessible for Ethan?

It was Ethan’s first day in first grade, and his parents felt a mix of excitement and nervousness as they walked him to school. Ethan, a bright and curious boy with autism, had spent his preschool years in a special education setting, where he thrived in smaller, more structured environments. But this year, his parents, his teachers, and the school team had decided to try something different—Ethan would be included in a general education classroom for the first time.

Ethan loved routine and predictability, so the idea of a new classroom filled him with apprehension. The sounds, the voices, and the hustle of a typical first-grade classroom were overwhelming to him. He had a hard time sitting still for long periods and struggled with transitions, especially when the class moved from one activity to the next.

As Ethan entered the classroom, Mrs. Green, his teacher, greeted him with a warm smile. “Good morning, Ethan! We are so happy you’re here,” she said, crouching down to his level. Beside her stood Ms. Sara, the special education aide, who would be working with Ethan throughout the day. She was there to help him stay focused and provide the support he needed.

The first few minutes were tough. Ethan hesitated at his desk, clutching his favorite sensory toy—a small rubber ball. He looked around, his wide eyes scanning the room full of children chatting and settling into their seats. The noise felt too loud for him.

Mrs. Green had prepared the class for Ethan’s arrival, explaining to the students that Ethan learns a little differently and might need some extra help. She asked everyone to be kind and patient, and her words set the tone for the day.

As the class began their morning circle, Ethan sat with Ms. Sara, who gently guided him to participate in the discussion. He wasn’t quite ready to speak, but he watched intently as the other children raised their hands to answer questions about the day’s theme: “All About Me.” Mrs. Green noticed Ethan’s attention and encouraged him to share when he was ready.

It wasn’t long before Ethan’s moment came. Mrs. Green asked the students to talk about their favorite animals. Ethan, who had always been fascinated by sea creatures, raised his hand, gripping the rubber ball tightly. “I like dolphins,” he said quietly, but with excitement in his voice. His classmates turned and smiled at him, nodding in approval.

“Dolphins are awesome!” one of the students said. “I love dolphins too!”

For the rest of the day, Ethan continued to engage in small ways—sometimes quietly, sometimes more exuberantly, depending on how he was feeling. When the class transitioned to art, Ms. Sara helped him with a few extra prompts to keep him focused, and by lunchtime, he was sitting with two classmates, sharing his favorite snack and laughing along with their stories.

It wasn’t a perfect day. There were moments when Ethan became overwhelmed by the noise or by changes in the routine, and he needed to take a break in a quiet space with Ms. Sara. But for the most part, he was able to participate in the general education program alongside his peers, and he wasn’t the only one who learned something that day.

Mrs. Green made sure to celebrate each little victory, whether it was Ethan answering a question or simply managing a transition from one activity to another. By the end of the day, Ethan was smiling as he headed home, telling his parents about his new friends and how he got to talk about dolphins in front of the whole class.

His parents, overwhelmed with pride, knew this was just the beginning of an exciting journey. The school year ahead would have its challenges, but Ethan was making strides toward being part of something bigger. He wasn’t just part of a special program anymore; he was part of a class—a community where he could grow, learn, and thrive just like every other child.

In the months that followed, Ethan’s confidence grew. With the support of his classmates, Mrs. Green, and Ms. Sara, he became more comfortable in the classroom, learning to navigate its sounds, routines, and expectations. It wasn’t always easy, but every day, Ethan took another step toward finding his place in the world.

Accommodations

Accommodations are an essential strategy to support diverse learners within the classroom. They involve changes to how a student accesses information or demonstrates knowledge without altering the curriculum itself. Examples include:

- Providing extra time for tests and assignments.

- Offering materials in varied formats, such as audio recordings or visual aids.

- Allowing the use of assistive technology, like speech-to-text software.

These strategies help ensure that all students, regardless of their learning styles or challenges, can engage with the curriculum effectively.

Modifications

In contrast, modifications involve altering the curriculum or learning expectations to meet the needs of specific students. This might include simplifying assignments, changing grading criteria, or offering alternative assessments. Modifications are especially critical for students with significant learning differences, ensuring that educational goals remain attainable and relevant (U.S. Department of Education, 2020).

By implementing both accommodations and modifications, educators can cultivate an inclusive classroom environment that acknowledges and supports the diverse learning styles of all students. This approach not only enhances educational experiences but also fosters a sense of belonging and engagement among learners.

Assistive technology (AT)

Assistive Technology refers to any device, software, or system that helps students, particularly those with disabilities, to access the curriculum, participate in classroom activities, and achieve academic success. These tools can range from simple low-tech devices to advanced high-tech systems, and they are used to support students’ individual needs, whether those needs are related to physical, sensory, cognitive, or learning challenges.

Types of Assistive Technology Used in Elementary Schools:

- Low-Tech Assistive Tools:

- Graphic Organizers: Tools like visual aids, diagrams, or charts help students organize their thoughts, plan writing tasks, or break down complex concepts.

- Colored Overlays: Transparent colored sheets placed over reading materials to help students with visual impairments or dyslexia better focus and read text.

- Pencil Grips: Special grips for pens or pencils to help students with fine motor difficulties hold writing instruments more comfortably.

- Mid-Tech Tools:

- Audio Recorders: Simple recording devices or apps that allow students to record their thoughts or instructions, helping those with writing difficulties, such as dysgraphia, or for students who struggle with remembering verbal instructions.

- Word Processors: Word processing programs like Microsoft Word that include speech-to-text capabilities, spell-checking, and word prediction, which assist students with writing difficulties.

- High-Tech Tools:

- Text-to-Speech Software: Tools like Kurzweil or Read&Write convert text into spoken words, making it easier for students with reading difficulties (e.g., dyslexia) to access written materials.

Apply

Read the following anecdotes and answer the questions.

- Which scenario shows how a teacher makes a modification and which shows an accommodation? Use the explanation above to justify your answer.

- Explain how education is no longer “One size fits all” and use examples from the scenarios to support your answer.

- What assistive technology might be used in each scenario and how?

Scenario 1:

In Mrs. Green’s third-grade class, the students were given an assignment to write a short report on an animal. They were supposed to research their animal, write down interesting facts, and then present what they learned in a few paragraphs. Most of the students were excited about the project, but one student, Max, felt nervous. Max loved animals, but he didn’t like writing. He often found it hard to sit down and write long sentences and would get frustrated when he couldn’t explain his thoughts clearly on paper.

One day, Mrs. Green noticed Max was looking upset and decided to talk to him after class. Max told her how much he loved animals but how hard it was for him to write the report. He was worried he wouldn’t be able to finish it.

Mrs. Green thought for a moment and then smiled. “Max, I have an idea,” she said. “How about instead of writing a report, you create a poster about your animal? You can draw pictures and write a few facts. You can still tell me everything you’ve learned, but you’ll do it in a way that feels more fun and less stressful.”

Max’s face lit up. He loved drawing and thought the poster idea sounded perfect. Mrs. Green explained that he could include pictures of his animal, labels showing where it lives, what it eats, and any special facts. He could even use bright colors to make it interesting for everyone to see.

Over the next week, Max worked hard on his poster. He drew a big picture of his animal, a wolf, running through the forest. He added fun facts like, “Wolves live in packs” and “Wolves can run up to 35 miles per hour!” Max was proud of his work and even showed his classmates a few sneaky wolf facts as he worked.

When it was time to present, Max stood up in front of the class with his poster. He shared what he had learned about wolves, and everyone was amazed at how much information he knew. His classmates loved the pictures, and Max felt proud of what he had done. Mrs. Green praised him for his creativity and for using his own way to share his learning.

Thanks to Mrs. Green’s idea, Max was able to complete the project in a way that worked for him. It reminded him that there are many ways to show what you know, and sometimes making small changes to an assignment can help everyone shine in their own special way.

Scenario 2

In Mrs. Lopez’s third-grade class, it was time for the students to take their weekly spelling test. Most of the students seemed excited to show how well they knew their words, but one student, Lily, was feeling a little anxious. Lily had dyslexia, which made it difficult for her to read and spell words the way most of her classmates did. While she understood the words when she heard them, writing them down was a challenge.

As Mrs. Lopez began handing out the spelling tests, she noticed that Lily was staring at the paper, looking a little overwhelmed. Mrs. Lopez had learned about Lily’s challenge and knew that she needed to provide an accommodation to help her succeed. Instead of simply handing Lily the test like the other students, Mrs. Lopez quietly pulled Lily aside and gave her a special arrangement. She offered to read the words out loud to her one at a time, allowing her to focus on spelling without having to struggle with reading them off the paper.

Lily smiled with relief as Mrs. Lopez carefully pronounced each word, giving her time to think and write. With this small change, Lily was able to focus on what she knew and do her best without feeling stressed. She wrote down the words with more confidence, remembering how they sounded rather than struggling with the letters on the page.

When the test was over, Lily’s results were much better than she had expected. Mrs. Lopez praised her for doing such a great job, and Lily felt proud of her accomplishment. The accommodation helped her show what she knew without letting her dyslexia get in the way.

Mrs. Lopez understood that every student learns in their own way, and sometimes a simple adjustment — like reading aloud the test — can make all the difference in helping a student succeed.

Response to Intervention (RTI)

Response to Intervention (RTI) is a multi-tiered approach used in schools to identify and support students who are struggling with academic or behavioral difficulties. RTI focuses on providing early, systematic interventions to help students succeed, and it uses ongoing monitoring of students’ progress to guide decision-making about the intensity of the interventions needed.

Key Components of RTI:

Universal Screening

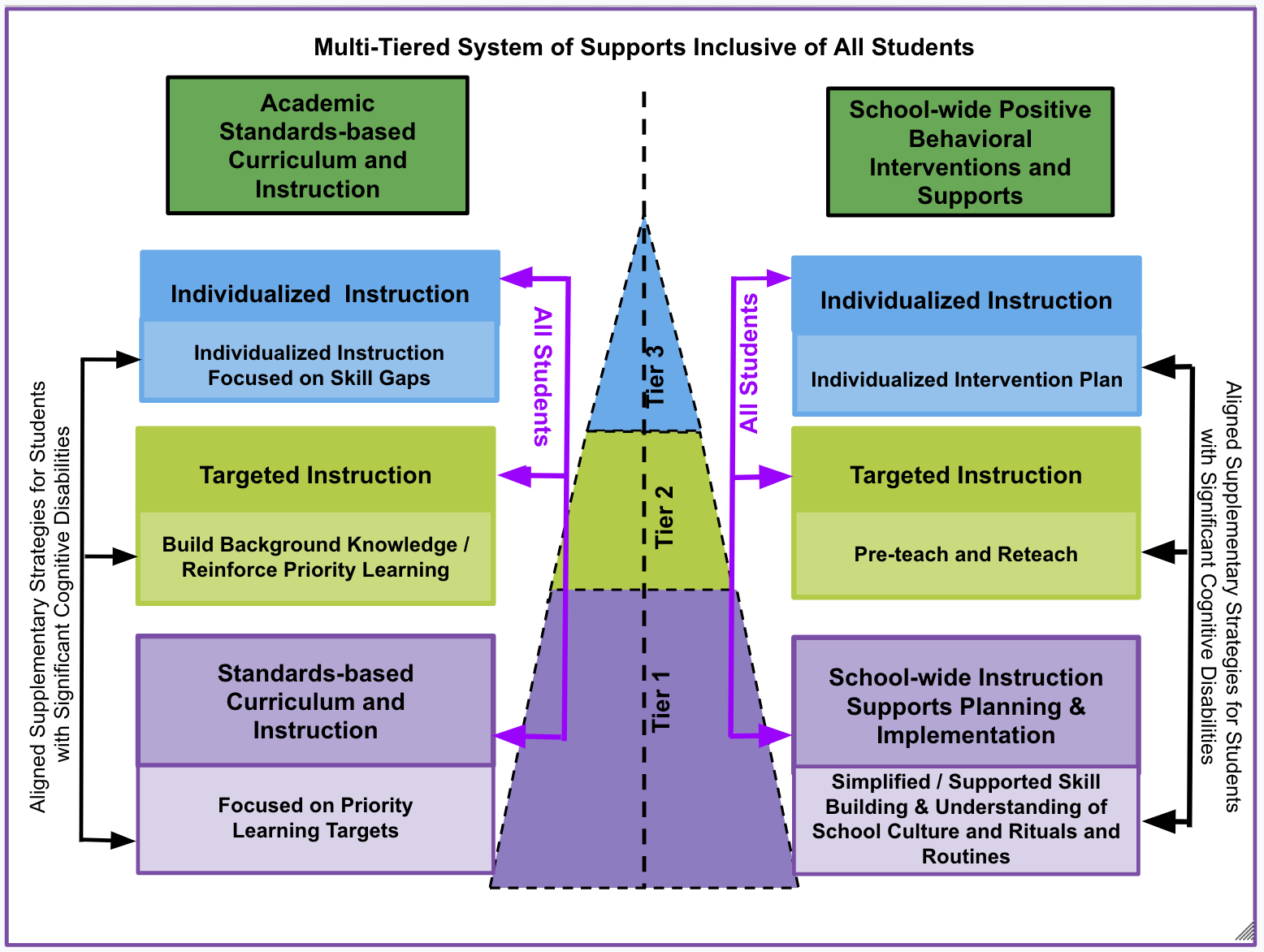

At the beginning of the school year, all students are screened to assess their current level of academic performance or behavioral functioning. This helps identify students who may be at risk for falling behind or who need additional support. These screenings are typically brief assessments that evaluate key areas such as reading, math, or social skills. This Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS) serves as an illustration of how instruction meets individual student needs.

Tiered Levels of Intervention:

RTI is structured into different levels, or tiers, of intervention, each designed to provide varying levels of support based on the student’s needs.

Tier 1 – Universal Instruction

Tier 1 consists of high-quality, evidence-based instruction provided to all students in the general education classroom (Fuchs & Fuchs, 2006). Teachers regularly monitor student progress and adjust instructional strategies to meet diverse learning needs. Most students respond well to this level of support.

Tier 2 – Targeted Interventions

Students who struggle despite Tier 1 instruction receive additional support through small-group interventions focused on specific skills, such as reading comprehension or math fluency (Vaughn & Fuchs, 2003). Progress is monitored more frequently to assess the effectiveness of interventions.

Tier 3 – Intensive Interventions

Students who do not make sufficient progress in Tier 2 receive highly individualized, intensive instruction, often in one-on-one or small-group settings (National Center on Response to Intervention, 2010). This level of support addresses significant learning difficulties, and ongoing monitoring helps determine whether special education services are necessary.

Progress Monitoring

Throughout RTI, student progress is systematically assessed to ensure interventions are effective. Educators use this data to adjust strategies as needed, preventing delays in support (Gersten et al., 2009).

Data-Driven Decision Making

Intervention decisions are based on objective data from assessments, progress monitoring, and teacher observations rather than intuition. If multiple interventions prove ineffective, students may be referred for specialized services, such as special education or further diagnostic assessments (Burns et al., 2016).

Goals of RTI

- Early Identification and Support:

- RTI aims to identify students who are struggling early on, allowing for quick interventions before academic or behavioral problems become too severe.

- Early intervention increases the likelihood that students will catch up to their peers and stay on track for academic success.

- Prevention:

- The RTI model is designed to prevent students from falling too far behind by providing interventions at the first signs of difficulty. Rather than waiting for a student to fail before intervening, RTI proactively addresses academic and behavioral challenges.

- Individualized Support:

- RTI provides tailored interventions that meet each student’s unique needs, ensuring that the support is appropriate to their level of difficulty. This helps maximize each student’s chance of success.

- Reduction in Referrals to Special Education:

- By providing effective interventions early, RTI aims to reduce the number of students who are inappropriately referred for special education services. Some students may simply need targeted, evidence-based interventions rather than formal special education.

Benefits of RTI:

- Timely Support: Students receive support as soon as they begin to struggle, rather than waiting for significant failure to be addressed.

- Flexibility: The approach allows teachers to adapt interventions based on the individual needs of the students.

- Data-Driven: Decisions are based on objective data, making it easier to track student progress and adjust strategies accordingly.

- Inclusion: RTI is typically delivered within the general education setting, allowing students to remain in the classroom environment while receiving the help they need.

Challenges of RTI:

- Time-Consuming: RTI can be resource-intensive, requiring significant time for screening, progress monitoring, and planning interventions.

- Teacher Training: Teachers must be well-trained in the RTI process, including how to use data effectively and provide interventions at each tier.

- Adequate Resources: Schools need to have the appropriate resources, such as trained staff and materials for interventions, to implement RTI successfully.

RTI and Special Education:

While RTI is a preventive approach, it also plays a role in the referral process for special education. If a student does not respond to interventions in Tier 1, 2, or 3, and continues to struggle despite targeted support, this may be an indication that the student has a disability and should be evaluated for special education services under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). RTI data often helps inform these evaluations.

Conclusion

Response to Intervention (RTI) is an essential framework used to support students who are struggling academically or behaviorally. By providing early, targeted interventions based on regular monitoring and data, RTI ensures that students receive the help they need at the right time. It’s a proactive approach that benefits all students by identifying and addressing difficulties early, helping to ensure better academic outcomes and fewer referrals to special education.

Diagnosing Disabilities

Although educators, teachers, and caregivers have experience working with a variety of children an their families, they are not qualified to diagnose disabilities. When signs and symptoms are identified, it is best to document the concerns and collaborate with families. Here are several important reasons to leave the diagnosing up to the professionals.

Lack of Specialized Training

Diagnosing a disability typically requires specialized knowledge and training in fields such as psychology, neurology, medicine, or special education. Teachers, while experts in pedagogy and classroom management, generally do not have the advanced education or clinical expertise required to identify or diagnose medical or psychological conditions. Disabilities, especially learning disabilities, ADHD, autism, or emotional disorders, often require complex assessments and an understanding of various diagnostic criteria.

Formal Diagnosis Requires Comprehensive Evaluation

A diagnosis involves a thorough evaluation process that includes:

- Standardized testing: Psychologists and other professionals administer formal, scientifically validated assessments to evaluate a child’s cognitive abilities, behavior, and academic skills.

- Observation and clinical interviews: Healthcare professionals often gather detailed background information from parents, teachers, and other caregivers.

- Medical examination: In some cases, medical tests are necessary to rule out other possible causes for the symptoms.

- Diagnostic criteria: Diagnoses follow the criteria outlined in diagnostic manuals, such as the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders), which teachers do not typically use in their practice.

Teachers may notice behaviors or struggles in students but do not have access to the complete assessment tools or protocols needed for an accurate diagnosis.

Role and Responsibilities of Teachers

- Teachers are trained to recognize academic difficulties and behavioral challenges in students and are skilled at providing support within the classroom setting. However, their role is to identify when a student might need additional help or support, not to make clinical decisions.

- Teachers are often the first to notice when a student is struggling, but their responsibility is to report concerns to appropriate professionals—such as school psychologists, special education staff, or healthcare providers—who are equipped to conduct proper assessments and make diagnoses.

- Teachers can recommend interventions and accommodations based on observed difficulties but must work with specialists to ensure that these strategies are appropriate for the student’s needs.

Legal and Ethical Boundaries

Diagnosing disabilities falls under the purview of licensed professionals, such as school psychologists, medical doctors, or clinical social workers, who have the legal authority to make such determinations. Teachers who attempt to diagnose disabilities without the appropriate qualifications risk overstepping their professional boundaries.

Legal protections, such as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), set forth specific processes for the identification of disabilities in schools. These processes require input from a team of professionals, and teachers are part of this team, but the actual diagnosis must be done by someone trained to do so.

The Importance of a Multidisciplinary Approach

Diagnosing a disability typically requires input from multiple professionals, including:

- School psychologists or clinical psychologists who can assess cognitive and emotional functioning.

- Speech-language pathologists if language or communication issues are present.

- Occupational therapists for motor skills or sensory issues.

- Medical professionals for conditions that might require medical intervention.

This collaborative approach ensures that the diagnosis is comprehensive and that the child’s needs are accurately understood.

Risk of Misdiagnosis

Without the appropriate expertise, teachers may unintentionally misinterpret a student’s behavior or struggles, leading to misdiagnosis. For example, a child who is struggling with math may not necessarily have a learning disability, but might instead be facing challenges such as anxiety or a language barrier. Similarly, behaviors in children can sometimes be attributed to a disability when they might stem from other factors like trauma, stress, or undiagnosed health issues.

Conclusion

While teachers play a vital role in identifying early signs of potential learning challenges and advocating for appropriate interventions, they are not qualified to make formal diagnoses of disabilities. Diagnosing a disability requires specific, specialized training and a thorough, multidisciplinary evaluation. Teachers are best positioned to observe and report concerns, but the final diagnosis should come from a team of trained professionals who can provide the most accurate and comprehensive assessment of a child’s needs.

Apply

Read the following conversation between an teacher and parent, then answer:

- What mistake did the teacher make? How did it make the parent feel?

- What should have happened instead?

Teacher: [In a concerned tone] Hi, Mrs. Martinez. Thank you for coming in today. I’ve noticed some challenges with your son, Leo, in class recently, and I wanted to talk to you about it. He seems to have a lot of trouble focusing during lessons, and I’ve observed that he often seems restless, even disruptive at times.

Parent: [Worried] Oh no, that doesn’t sound like Leo. He’s always been a good kid at home. What do you mean by disruptive?

Teacher: Well, Leo frequently gets up from his seat, talks out of turn, and sometimes seems unable to sit still, even when we’re working on quiet tasks. I’ve seen these behaviors for a while, and after speaking with a few other teachers, I believe Leo might have Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). He exhibits all the classic signs, and based on my observations, I think it’s something we should address right away.

Parent: [Looking confused] ADHD? But Leo is so calm at home. He’s a little energetic, but I didn’t think it was anything more than being a typical boy. Could it be something else? Maybe he’s just having a hard time adjusting to school?

Teacher: [Confidently] Well, based on what I’ve seen in the classroom, it seems like ADHD is the most likely explanation. He’s not really able to focus on assignments for long, and sometimes he interrupts his classmates when they’re speaking. It can be really disruptive, and I’ve tried different strategies, but they don’t seem to be working. I suggest we consider testing him for ADHD as soon as possible.

Parent: [Looking concerned but unsure] I’m not sure. I didn’t think Leo had any issues like that. Maybe he’s just having trouble adjusting to school. Could it be something related to his learning, like dyslexia or maybe just anxiety?

Teacher: [Interrupting] Honestly, it doesn’t sound like it’s related to anxiety or a learning disability. ADHD seems like the obvious answer. I think we should move forward with the testing and get him the help he needs.

Parent: [Hesitant, but still trusting the teacher] Okay, but should we consult someone else? Maybe a psychologist or someone who works with children specifically? I just want to be sure we’re on the right track before jumping to conclusions.

Teacher: [Dismissively] I’ve been teaching for a long time, and I know the signs. I’m confident this is ADHD, and the sooner we start with the testing, the better. We don’t want him to fall further behind, and treatment can make a huge difference. I’ll go ahead and send in the referral forms.

Parent: [Worried, but unsure about next steps] Alright, I guess we’ll start with the testing, but I just want to make sure we’re not missing anything else, especially if Leo is struggling with something different.

Person-First vs. Identity First Language

Person First Language

This is an approach to communication that emphasizes the individual before their disability. It is grounded in the belief that people are not defined by their disabilities, but rather by their unique qualities as individuals. This language encourages respect, dignity, and the understanding that the disability is just one part of a person’s identity.

Key Principles of Person-First Language

- Focus on the person: The person is always placed before their disability or condition. For example, instead of saying “autistic child,” person-first language encourages saying “child with autism.” The focus is on the person first, not the disability.

- Respectful and neutral tone: Person-first language seeks to avoid negative or limiting language. Words like “suffering from,” “victim of,” or “handicapped” are avoided because they can imply that the disability is the defining or negative aspect of the person’s life.

- Highlighting the individual, not the disability: It is important to convey that a person is more than their condition. For example, instead of referring to someone as “a disabled person,” you would say “a person with a disability.”

Examples of Person-First Language

- Person with autism instead of autistic person.

- Individuals with a learning disability instead of learning disabled persons.

- Person with a physical disability instead of crippled person.

- Person with a visual impairment instead of blind person.

- Person who uses a wheelchair instead of wheelchair-bound.

Why Person-First Language Matters

- Empathy and respect: It reflects a mindset that focuses on the individual rather than labeling or defining them by their disability.

- Promotes inclusion: Person-first language fosters a more inclusive environment, reminding us that everyone has a range of characteristics beyond their disabilities.

- Empowers individuals: By acknowledging the person first, it gives them agency and affirms their dignity, avoiding the reduction of a person’s identity to a condition or limitation.

Identity First Language

Identity-first language, in contrast, acknowledges that a disability can be an integral part of a person’s identity and self-definition. It is often preferred by individuals who see their disability as a source of strength, pride, or a shared experience within a community.

Key Principles of Identity-First Language

- The Identity comes first: Identity-first language places the person’s condition or identity before the person (e.g., “autistic person” rather than “person with autism”). It reflects that the identity is a core part of who they are—not something separate or negative.

- Affirms group pride and cultural identity: Many individuals and communities prefer identity-first language because it validates and embraces their lived experience as something integral, not something to be avoided or minimized.

- Community preference matters; Using identity-first language respects the preferences of individuals and communities. It’s important to ask or research how a person or group self-identifies, demonstrating empathy and cultural sensitivity.

Examples of Identity-First Language:

- Disabled person instead of person with a disability

- Autistic person instead of person with autism

- Deaf person instead of person who is deaf

Why Identity-First Language Matters:

- Demonstrates Empathy and Respect: It honors how people see themselves and avoids framing identity as a deficit or burden.

- Promotes Inclusion: It fosters understanding and acceptance by recognizing diverse ways of being as valid and valued.

- Empowers Individuals: It supports self-advocacy by affirming that people can take pride in their identity.

- Avoids Stigmatization: It shifts the narrative from “something is wrong with you” to “this is part of who you are.”

- Builds Trust: Using preferred language shows genuine care and a willingness to listen and learn.

In Practice:

While person-first language is widely recommended, it’s important to note that some individuals or groups within the disability community may prefer identity-first language (e.g., autistic person, Deaf community), as they feel that their disability is an intrinsic and important part of who they are. Thus, it’s important to respect individuals’ preferences when using language.

The most important aspect is to respect the individual’s preference. If unsure, it is best to ask the individual how they prefer to be identified.

Key Terms

- Multiple Intelligences

- IDEA (Individuals with Disabilities Act)

- FAPE (Free and Appropriate Education)

- LRE (Least Restrictive Environment)

- Accommodations

- Modification

- Assistive Technology

- (RTI) Response to Intervention

- Person First Language

Conclusion

Understanding learning styles through the frameworks of multiple intelligences, IDEA, and the application of accommodations and modifications is vital for creating equitable and effective educational environments. By recognizing and addressing the varied ways in which students learn, educators can create an atmosphere where all children can thrive, ensuring that every learner has the opportunity to reach their full potential.

References

- Burns, M. K., Appleton, J. J., & Stehouwer, J. D. (2016). Meta-analytic review of response-to-intervention research: Examining field-based and research-implemented models. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 34(5), 437-452.

- Fuchs, D., & Fuchs, L. S. (2006). Introduction to response to intervention: What, why, and how valid is it? Reading Research Quarterly, 41(1), 93-99.

- Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. Basic Books.

- Gersten, R., Compton, D., Connor, C. M., Dimino, J., Santoro, L., Linan-Thompson, S., & Tilly, W. D. (2009). Assisting students struggling with reading: Response to Intervention (RTI) and multi-tier intervention for reading in the primary grades. Institute of Education Sciences.

- National Center on Response to Intervention. (2010). Essential components of RTI: A closer look at response to intervention. U.S. Department of Education.

- Thurlow, M. L., Ghere, G., Lazarus, S. S., & Liu, K. K. (2020, January). MTSS for all: Including students with the most significant cognitive disabilities. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes/TIES Center.

- U.S. Department of Education. (2020). A Guide to the Individualized Education Program. Retrieved from https://www.ed.gov/parents/needs/speced/iepguide/index.html

- Vaughn, S., & Fuchs, L. S. (2003). Redefining learning disabilities as inadequate response to instruction: The promise and potential problems. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 18(3), 137-146.

Media Attributions

- MTSS Graphic- 1-3-20_opt © National Center on Educational Outcomes adapted by TIES Center is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license