14 Guiding Behavior

How to be an Effective Teacher

Tanessa Sanchez and Kerry Diaz

Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter, you should be able to:

Guiding behavior in school-age children is a fundamental aspect of their development and education. Effective behavior guidance promotes positive social interactions, fosters emotional well-being, and supports academic success. This chapter explores key concepts related to guiding behavior, including self-esteem and behavior, conflict resolution, social skill development, special concerns, and the responsibilities of the environment and teachers.

Self-Esteem and Behavior

Self-esteem, the perception of one’s own worth, plays a crucial role in children’s behavior. Children with healthy self-esteem are more likely to engage positively with peers, take risks in learning, and handle challenges effectively.

Importance of Self-Esteem

- Influence on Behavior: High self-esteem is associated with positive behaviors, such as cooperation, resilience, and willingness to try new activities. Conversely, low self-esteem can lead to negative behaviors, including withdrawal, aggression, or acting out in class (Harter, 1999).

Example: A child with high self-esteem may participate actively in group discussions, whereas a child with low self-esteem might avoid contributing, fearing negative evaluation. - Supportive Environment: Caregivers and educators can enhance children’s self-esteem through positive reinforcement, constructive feedback, and fostering a sense of belonging. A supportive environment encourages children to express themselves and take pride in their achievements (Branden, 1994).

Example: Celebrating small successes in a classroom, such as completing a project or helping a peer, reinforces a child’s sense of competence and worth.

Conflict Resolution

Conflict is a natural part of social interactions, and teaching children effective conflict resolution skills is vital for their social development. Conflict resolution involves helping children navigate disagreements in a constructive manner.

Key Strategies

- Modeling Behavior: Educators can model effective conflict resolution strategies, demonstrating how to approach disagreements calmly and respectfully.

Example: When conflicts arise in the classroom, a teacher might illustrate the steps to resolution: expressing feelings, listening to the other person, and finding a compromise. - Role-Playing: Engaging children in role-playing scenarios can help them practice conflict resolution skills in a safe environment. This hands-on approach allows children to explore different perspectives and solutions.

Example: A teacher sets up a role-playing activity where children practice resolving a conflict over sharing toys, encouraging them to brainstorm solutions together. - Establishing Ground Rules: Creating a classroom culture with clear expectations for behavior can prevent conflicts from escalating. Ground rules should emphasize respect, active listening, and the importance of discussing feelings.

Example: At the beginning of the school year, a teacher works with students to create a list of ground rules, ensuring that all voices are heard and considered.

Social Skill Development

Social skills are essential for successful interactions with peers and adults. These skills include communication, cooperation, and empathy, which are foundational for building healthy relationships.

Strategies for Development

- Structured Activities: Engaging children in group activities fosters social skills by encouraging cooperation and communication. Activities like team sports, group projects, or cooperative games promote collaboration.

Example: A caregiver organizes a group game that requires teamwork, such as a relay race, allowing children to practice working together and supporting one another. - Teaching Empathy: Educators can explicitly teach empathy by discussing emotions and modeling empathetic responses. Children can learn to recognize and understand the feelings of others.

Example: A teacher reads a story about friendship and prompts a discussion about how different characters might feel, guiding children to relate those feelings to their own experiences. - Positive Reinforcement: Reinforcing positive social behaviors encourages children to continue using them. Acknowledging cooperative behavior or acts of kindness helps solidify these skills.

Example: A teacher praises a child who shares a toy with a peer, reinforcing the importance of generosity and cooperation.

Special Concerns

Certain factors may complicate behavior guidance, including developmental disabilities, trauma, and cultural differences. Educators must be equipped to address these special concerns to effectively support all children.

Strategies for Addressing Special Concerns

- Individualized Support Plans: For children with developmental disabilities, personalized plans may be necessary to address specific behavioral challenges. Collaborating with specialists can provide tailored strategies.

Example: A child with autism may benefit from a behavior intervention plan that includes visual supports and clear, consistent routines. - Trauma-Informed Practices: Understanding the impact of trauma on behavior is essential. Educators should adopt trauma-informed practices that prioritize safety, trust, and emotional support.

Example: A teacher creates a calm and predictable classroom environment to help children who have experienced trauma feel secure. - Cultural Sensitivity: Recognizing and respecting cultural differences in behavior and communication styles is crucial. Educators should seek to understand the diverse backgrounds of their students and adapt their approaches accordingly.

Example: A teacher learns about cultural norms that influence communication styles and adapts classroom discussions to be more inclusive.

Trauma-Informed Practices in Schools

Trauma-informed practices in schools recognize the profound impact of trauma on students and aim to create a safe, supportive, and responsive learning environment. Trauma can result from various experiences, such as abuse, neglect, family instability, violence, or chronic stress. When schools adopt a trauma-informed approach, they prioritize relationships, emotional regulation, and resilience-building, helping students feel secure, valued, and understood. By implementing these practices, schools can foster both emotional well-being and academic success.

A trauma-informed approach is guided by several key principles. Safety is the foundation, ensuring that students feel both physically and emotionally secure. This involves creating structured classroom routines, maintaining clear expectations, and designing a predictable environment that reduces anxiety. Trust and transparency are equally important, as students thrive when they have reliable relationships with educators who communicate honestly and consistently. Positive peer and staff relationships further enhance a trauma-sensitive environment by fostering connections and a sense of belonging. Schools that encourage collaborative learning and mentorship help students develop social skills and emotional support systems.

Another essential principle is empowerment and student voice. Giving students choices in their learning process helps them regain a sense of control, which is often diminished in traumatic experiences. Encouraging self-advocacy and decision-making builds confidence and independence. Additionally, social-emotional learning (SEL) plays a crucial role in trauma-informed education by teaching students coping strategies, self-awareness, and emotional regulation. Incorporating mindfulness, breathing exercises, and conflict resolution strategies helps students manage stress and emotions effectively.

Cultural sensitivity and inclusivity also contribute to a trauma-informed school culture. Recognizing diverse backgrounds and experiences ensures that all students feel respected and included. Schools should implement inclusive teaching practices that honor students’ identities and unique needs. Furthermore, collaboration with families and the community strengthens trauma-informed support. Schools can work with parents, guardians, and local organizations to provide counseling, mentorship, and social services for students who need additional resources.

There are several practical strategies educators can implement to support trauma-affected students. Predictability and structure are essential, so using visual schedules and maintaining consistent routines can help reduce students’ anxiety. Safe spaces, such as calm-down corners or quiet areas, allow students to self-regulate when overwhelmed. Positive reinforcement focuses on strengths and progress rather than punishment-based discipline, which can further traumatize students. Teaching self-regulation skills, such as deep breathing, movement breaks, or journaling, can help students manage their emotions more effectively. Educators should also be mindful of potential trauma triggers, such as loud noises or sudden changes, and work to create a calm and understanding classroom environment.

Flexible learning approaches are another key aspect of trauma-informed education. Allowing students to engage with material in multiple ways—through hands-on activities, group work, or independent projects—helps accommodate different learning needs. Encouraging a growth mindset is also beneficial, as it teaches students to see challenges as opportunities for learning rather than failures.

The benefits of trauma-informed practices extend beyond the classroom. Students who receive trauma-sensitive support develop better emotional regulation and coping skills, reducing behavioral challenges. A safe and supportive environment improves focus, motivation, and academic performance. Additionally, these practices strengthen relationships between students, teachers, and peers, fostering a positive school culture. By reducing stress and anxiety, trauma-informed strategies also help students feel more engaged and ready to learn. Most importantly, trauma-informed schools equip students with the resilience and life skills they need to succeed both in and outside the classroom.

By implementing trauma-informed practices, schools become more than just places of education—they become places of healing and growth. Creating a nurturing environment that acknowledges trauma and supports students’ needs empowers them to overcome challenges and reach their full potential.

Restorative Practices

Restorative practices in schools focus on repairing harm, strengthening relationships, and fostering a positive school climate rather than relying solely on punishment. This approach emphasizes accountability, empathy, and dialogue, helping students understand the impact of their actions and take responsibility for them. By prioritizing relationship-building, restorative practices create an environment where students, teachers, and staff engage in open communication and mutual respect.

Common strategies include restorative circles, where groups discuss concerns and conflicts, and restorative conferences, which bring together those involved in an incident to repair harm. Peer mediation allows trained students to help their peers resolve disputes, while affective statements and questions encourage reflection on behavior and its effects. Repair agreements provide structured ways for students to make amends, such as through apologies or acts of service.

Implementing restorative practices leads to numerous benefits, including reduced suspensions and expulsions, improved school climate, and enhanced conflict resolution skills. This approach fosters a culture of trust and inclusion, encouraging students to grow personally and take responsibility for their actions. By shifting from a punitive model to one centered on restoration, schools create a supportive and respectful community where students feel valued and heard.

Token Economy

A token economy in the classroom is a behavioral management system that uses tokens as a form of reinforcement to encourage desired behaviors. Students earn tokens—such as points, stickers, or fake money—for demonstrating positive behaviors like completing assignments, following rules, or helping others. These tokens can later be exchanged for rewards, such as extra recess, small prizes, or privileges.

Token economies rely on extrinsic motivation, meaning that students are motivated by external rewards rather than internal satisfaction. This can be effective in shaping behavior, especially for younger students or those who need additional structure. Over time, the goal is to help students internalize positive behaviors so they continue them even without rewards.

However, there are potential negative effects of token economies. One concern is that students may become dependent on external rewards and struggle to stay motivated without them. This can reduce intrinsic motivation, where students engage in tasks for personal satisfaction rather than external incentives. Additionally, some students may feel discouraged if they consistently fail to earn tokens, leading to frustration or disengagement. In some cases, token economies can also create an overly competitive environment, where students compare their rewards and feel pressured or excluded.

Routines and Procedures

Routines and procedures in a classroom are structured expectations that guide students on how to behave and complete daily tasks efficiently. They create a sense of order, consistency, and predictability, helping students feel secure and focused. Well-established routines minimize disruptions, maximize instructional time, and promote independence by ensuring students know what is expected of them in various situations.

Examples of classroom routines and procedures

- Morning Arrival Routine: Students enter the classroom, unpack their bags, place homework in a designated spot, and begin a warm-up activity or morning work.

- Attendance and Lunch Count: A systematic way for students to check in, such as moving their name card to “present” or responding to a roll call.

- Transitioning Between Activities: Clear signals, such as a countdown or clapping pattern, to help students smoothly move from one task to another.

- Lining Up and Walking in Hallways: Expectations for quiet, orderly movement in line, such as standing in a straight line and facing forward.

- Bathroom and Water Break Procedures: A method for requesting and taking breaks, such as using a sign, hall pass, or silent hand signal.

- Turning in Assignments: A designated location, such as a bin or tray, for students to submit completed work.

- Getting Attention (Quiet Signal): A consistent signal, like raising a hand, using a countdown, or ringing a bell, to regain students’ attention.

- End-of-Day Dismissal Routine: Steps for packing up, cleaning the area, and lining up to leave in an orderly fashion.

- Classroom Supply Usage: Rules for borrowing, returning, and organizing classroom materials like pencils, books, and technology.

- Handling Conflicts or Questions: A structured way for students to ask for help, such as raising their hand, writing a note, or using a peer problem-solving strategy.

By establishing and practicing routines, teachers create a structured learning environment that fosters independence, efficiency, and respect.

Visual Schedule

A visual schedule is a tool that uses pictures, symbols, words, or a combination of these to outline the sequence of activities or tasks in a classroom. It provides a clear, structured representation of the daily routine, helping students understand what to expect and when transitions will occur. Visual schedules are especially beneficial for young children, students with disabilities (such as autism or ADHD), and English language learners, as they reduce anxiety, enhance independence, and improve time management.

A typical visual schedule may include icons or images representing activities such as morning work, math, recess, lunch, and dismissal. These schedules can be displayed on a classroom board for the whole group or personalized for individual students using a binder or digital device. Some visual schedules are interactive, allowing students to move a marker or remove completed tasks, giving them a sense of accomplishment and structure.

By using a visual schedule, teachers create a predictable and supportive learning environment where students feel more confident and engaged. It minimizes confusion, decreases behavioral issues related to uncertainty, and helps students smoothly transition between tasks.

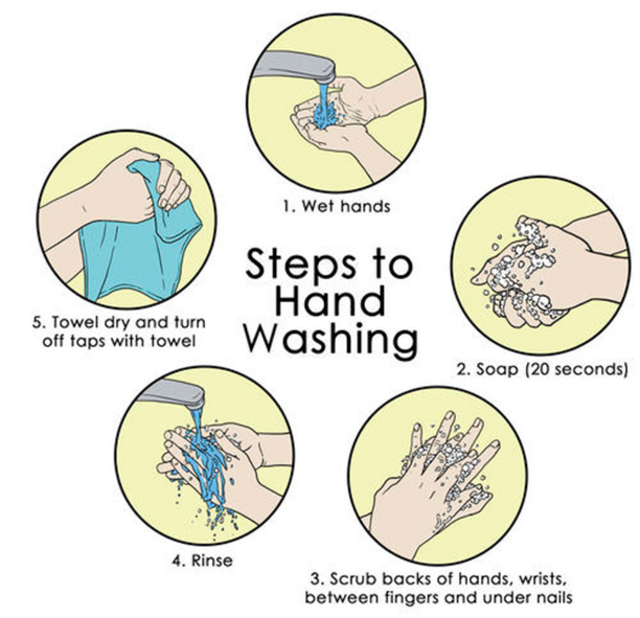

Visual Procedure

A visual procedure is a step-by-step guide using pictures, symbols, or written instructions to help students complete a task independently. It visually breaks down a process into manageable steps, making it easier for students to follow directions and stay on track. Visual procedures are commonly used for routines like handwashing, lining up, completing assignments, or transitioning between activities.

For example, a visual procedure for handwashing might include:

- Turn on the water

- Wet hands

- Apply soap

- Scrub hands for 20 seconds

- Rinse

- Dry hands

Visual procedures help students, especially young learners and those with special needs, understand expectations and build independence by following structured, predictable steps.

The First Days of School

The First Days of School is a widely used guide for teachers, focusing on effective classroom management and student success. The book emphasizes that the first days of school set the tone for the entire year and provides strategies to create a structured, positive learning environment.

The authors highlight three key characteristics of effective teachers: having good classroom management, delivering engaging lessons, and maintaining high expectations for students. They stress the importance of routines and procedures, ensuring that students understand expectations for behavior, transitions, and daily tasks. The book also discusses building relationships with students, fostering a respectful and encouraging atmosphere.

Another major theme is lesson mastery, where teachers design clear objectives, engage students actively, and assess learning effectively. The authors encourage teachers to be lifelong learners, continuously improving their teaching methods.

With practical tips, real-world examples, and step-by-step strategies, The First Days of School serves as a valuable resource for both new and experienced teachers aiming to create a structured, successful, and student-centered classroom.

Watch

Take a few moments to watch the following video on classroom discipline and procedures by Harry Wong, the author of The First Days of School. See if you can identify what constitutes an effective teacher.

Building Relationships with Students

Building strong relationships with students is essential for effective classroom management. When students feel respected, valued, and connected to their teacher, they are more likely to be engaged, motivated, and cooperative. Positive relationships foster trust, reduce behavioral issues, and create a supportive learning environment where students feel safe to take risks and express themselves.

Activities to build relationships with students

- Morning Greetings: Greet each student at the door with a smile, handshake, high-five, or personalized greeting to start the day positively.

- Get-to-Know-You Games: Play activities like “Two Truths and a Lie” or “Would You Rather?” to help students and teachers learn about each other.

- Student Interest Surveys: Have students fill out a short questionnaire about their hobbies, favorite books, music, and learning preferences to show interest in their lives.

- Class Meetings: Hold regular meetings where students can share thoughts, discuss classroom concerns, and celebrate successes.

- Lunch with the Teacher: Invite small groups of students to eat lunch with you in the classroom to chat in a relaxed setting.

- Shout-Out Wall or Jar: Create a space where students can leave positive notes about their classmates, encouraging kindness and recognition.

- Personalized Notes or Check-Ins: Write a quick note or take a moment to check in with students who need extra support or encouragement.

- Cooperative Learning Activities: Use team-building exercises and group projects to foster collaboration and strengthen relationships.

- Student-Choice Activities: Give students opportunities to choose assignments, topics, or seating arrangements to empower them and show respect for their preferences.

- Classroom Traditions: Establish fun routines like “Motivational Monday,” “Fun Fact Friday,” or “Student of the Week” to create a sense of community.

By consistently engaging in these activities, teachers build meaningful connections with students, leading to a more positive and well-managed classroom environment.

Conclusion

Guiding behavior in school-age children involves a multifaceted approach that includes fostering self-esteem, teaching conflict resolution, promoting social skills, addressing special concerns, and creating a supportive environment. Educators play a vital role in this process, equipping children with the tools they need to navigate their social worlds successfully.

References

- Branden, N. (1994). The Six Pillars of Self-Esteem. Bantam Books.

- Harter, S. (1999). The development of self-representations. In Handbook of Child Psychology (Vol. 3). Wiley.

- Public School Character Development. (2015). Teacher Development Series: Classroom Discipline and Procedures. [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/rlwq4Nrh9Ic?si=zQh3C8jLDj2tOK8g

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton University Press.

- Wong, H. K., & Wong, R. T. (2018). The first days of school: How to be an effective teacher. Harry K. Wong Publications.

Media Attributions

- DEEB6366-D002-4A9F-9BBD-7E808015C5A3_1_105_c is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Visual Sched is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Steps_to_hand_washing © Projectoer adapted by Laura Guerin /CK-12 Foundation is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license