12 Families

Collaboration and Partnership

Tanessa Sanchez and Kerry Diaz

Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter, you should be able to:

Families play a pivotal role in children’s development, serving as the primary context in which they learn, grow, and form their identities. This chapter explores various aspects of families, including the changing nature of family structures, the importance of respecting diverse family forms, the effects of the home environment on children, effective communication with families, and how to assist families in accessing community resources.

Theoretical Connection

Brofenbrenner’s Ecological Model

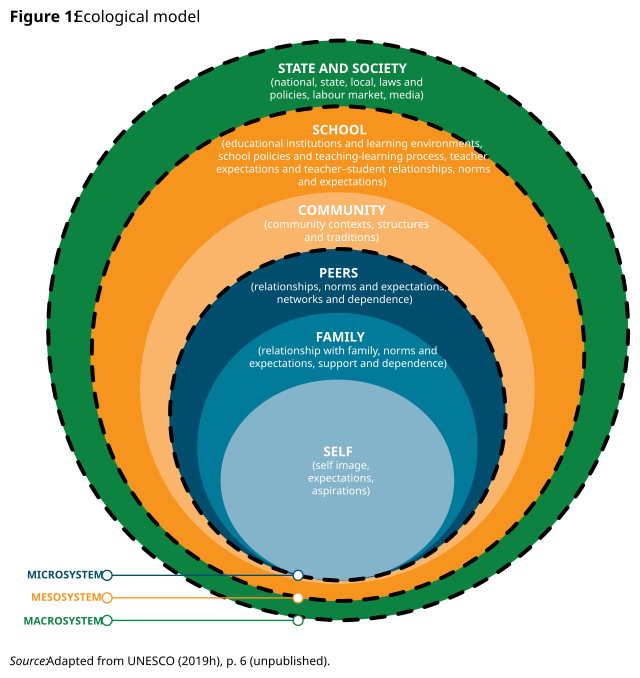

Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory explains how different environmental layers influence human development. Proposed by Urie Bronfenbrenner, this theory suggests that development is shaped by a complex interaction between an individual and their surroundings, which are organized into five interconnected systems. The microsystem is the closest layer, consisting of direct relationships such as family, school, peers, and caregivers. These interactions have an immediate impact on development, shaping behaviors and learning experiences. The mesosystem refers to the connections between different parts of the microsystem, such as how parental involvement in school influences a child’s academic performance. Strong, positive relationships between these systems can enhance development, while conflicts may hinder it.

Beyond direct interactions, the exosystem includes external environments that indirectly affect the individual, such as a parent’s workplace, neighborhood policies, or the influence of media. For example, a parent’s job loss can create financial stress that affects family dynamics and, in turn, the child. At a broader level, the macrosystem encompasses cultural and societal influences, including economic conditions, laws, and social values. A child raised in a society that prioritizes education will have different developmental experiences compared to one growing up in a society with limited access to schooling. Finally, the chronosystem considers the impact of time, accounting for both personal life transitions, such as parental divorce or moving to a new city, and historical events, like economic recessions or technological advancements. These factors influence development over a lifetime, shaping how individuals adapt to changes in their environment.

Overall, Bronfenbrenner’s theory highlights the dynamic and interconnected nature of development, emphasizing that human growth is influenced by a combination of immediate relationships, larger societal structures, and historical context. By understanding these systems, we can better analyze how external influences shape behavior, learning, and overall well-being. Would you like a specific application of this theory, such as in education, psychology, or parenting?

The Five Ecological Systems:

- Microsystem (Immediate Environment)

- The closest layer to the individual, consisting of direct relationships and interactions.

- Examples: Family, school, peers, teachers, and caregivers.

- Impact: A child’s development is directly influenced by interactions within this system, such as parental care or school experiences.

- Mesosystem (Connections Between Microsystems)

- Represents the interactions between different parts of the microsystem.

- Examples: A child’s home life affecting school performance, or parents interacting with teachers.

- Impact: Strong connections can provide support, while conflicts (e.g., parental conflict affecting school behavior) can hinder development.

- Exosystem (Indirect Influences)

- Environments that indirectly affect an individual, even though they are not directly involved.

- Examples: A parent’s workplace, media, neighborhood policies, and extended family.

- Impact: A parent losing a job (workplace stress) may affect family dynamics and, in turn, the child’s well-being.

- Macrosystem (Cultural and Societal Influences)

- Encompasses broader societal factors like culture, laws, economic systems, and ideologies.

- Examples: Societal values on education, religious beliefs, and government policies.

- Impact: A child growing up in a society that values education will have different opportunities than one in a society with limited access to schooling.

- Chronosystem (Changes Over Time)

- Represents the influence of time, both in personal life (life transitions) and historical context.

- Examples: Moving to a new country, changes in family structure (divorce, death), economic recessions, and technological advancements.

- Impact: A child’s development may be influenced differently depending on the era they grow up in, such as growing up during the digital age versus the pre-Internet era.

Changing Families

The concept of family has evolved significantly over the past few decades. Traditional family structures, often defined as a two-parent household with children, are increasingly complemented by diverse arrangements, including single-parent families, blended families, and families headed by same-sex couples. According to the U.S. Census Bureau (2020), approximately 23% of children live with a single parent, and the number of same-sex couple households has risen markedly.

Examples of Changing Families

- Single-Parent Families: These families may result from divorce, separation, death, or the choice to raise children independently. Research indicates that children in single-parent households may face unique challenges, including economic stress and social stigma, but they can also thrive with strong support networks (Amato, 2000).

- Blended Families: Composed of parents who have remarried and brought children from previous relationships into the new household, blended families can create complex dynamics. Positive relationships among all family members can promote resilience and adaptability in children (Coleman & Ganong, 2004).

- Same-Sex Families: Families led by same-sex couples may face societal challenges but are increasingly recognized for providing stable, loving environments for children. Studies show that children raised in same-sex households fare just as well as those in heterosexual households in terms of social, emotional, and cognitive development (Patterson, 2006).

Family Structure Data from 2023 Census

According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2023 data on families and living arrangements, several notable trends in family structures have been observed:

Household Composition

- One-Person Households: In 2023, there were 38.1 million one-person households, accounting for 29% of all households. This marks a significant increase from 1960, when single-person households represented only 13% of all households.

Family Dynamics

- Families With Children: The proportion of families living with their own children under age 18 has been declining. In 2003, 48% of all families had their own children present in the household, compared to 43% in 2013 and 39% in 2023.

Marital Status and Living Arrangements:

- Never Married Adults: In 2023, 34% of adults aged 15 and over had never been married, an increase from 23% in 1950.

- Median Age at First Marriage: The estimated median age for first marriages in 2023 was 30.2 years for men and 28.4 years for women, up from 23.7 and 20.5 years, respectively, in 1947.

Children’s Living Arrangements:

- Two-Parent Households: In 2023, 75% of children under the age of 6 lived with two parents, whereas 68% of children aged 12 to 17 lived with two parents.

- Cohabiting Parents: Approximately 3.2 million children under 18 lived with cohabiting (unmarried) parents in 2023, a significant rise from 2.2 million in 2007.

Average Household and Family Size:

- Household Size: The average American household consisted of 2.51 people in 2023.

- Family Size: The average family size was 3.15 persons in 2023, a decrease from 3.7 in the 1960s.

These statistics reflect evolving family structures and living arrangements in the United States, influenced by factors such as delayed marriages, increased single-person households, and changing dynamics in child-rearing.

In 2023, single-parent families in the United States comprised a significant portion of households with children under 18. Key statistics include approximately 23% of children living in single-mother households, around 4% living in single-father households, and nearly 30% of all families with children under 18 being headed by a single parent, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

Respecting and Understanding Diverse Family Structures

Respecting and understanding diverse family structures is crucial for educators and caregivers. Each family brings unique strengths, traditions, and challenges that influence children’s development. Recognizing the value of diverse backgrounds fosters an inclusive environment where all families feel respected and understood.

Importance of Cultural Competence

Cultural competence involves understanding and appreciating the different values, beliefs, and practices of various families. For example, families from collectivist cultures may prioritize community and family cohesion over individual achievement, which can impact children’s behavior and expectations in educational settings (Hofstede, 2001). Educators should engage in ongoing cultural training to better understand the diverse backgrounds of their students and their families.

Interdependent vs Intradependent Family Values

Interdependent family values emphasize mutual reliance and cooperation among family members. In such families, members support each other emotionally, financially, and socially, with decision-making prioritizing the well-being of the group rather than individual desires. This value system is often found in collectivist cultures and extended family structures, where responsibilities are shared, and communication is open. For example, in a multigenerational household, grandparents may help raise children while working adults contribute financially and emotionally. The focus is on interconnectedness, ensuring that no one member is left to navigate challenges alone.

In contrast, intradependent family values promote self-reliance within the family unit, encouraging individual growth while maintaining familial bonds. This system is more common in nuclear families and individualistic cultures, where personal achievements and autonomy are emphasized. Family members provide emotional support but also prioritize personal responsibility and independence. For instance, a child may be encouraged to pursue higher education or a career independently while still maintaining close ties with their family. While both value systems foster strong family relationships, they differ in their balance between collective support and personal responsibility.

Effect of Home Environment on Children

The home environment significantly impacts a child’s development, influencing their emotional, social, and cognitive growth. Factors such as socioeconomic status, parental involvement, and the emotional climate of the home all contribute to children’s experiences and outcomes.

Key Influences on Development

- Socioeconomic Status (SES): Families with higher SES often have greater access to resources such as quality education, healthcare, and extracurricular activities. Conversely, lower SES can lead to stressors like food insecurity and limited access to educational support, which can negatively affect children’s academic performance and well-being (Duncan & Brooks-Gunn, 1997).

- Parental Involvement: Engaged parents who actively participate in their children’s education tend to foster higher academic achievement and better social skills. Strategies such as reading together, attending school events, and maintaining open communication about education can enhance parental involvement (Epstein, 2011).

- Emotional Climate: A positive home environment characterized by love, support, and open communication fosters secure attachments and emotional well-being in children. In contrast, a negative emotional climate, marked by conflict or neglect, can lead to behavioral issues and difficulties in social relationships (Cole et al., 2004).

Effective Communication with Families and Caregivers

Effective communication between educators and families is essential for supporting children’s development. Building strong relationships with families can enhance trust and collaboration, ultimately benefiting children’s learning experiences.

Strategies for Effective Communication

- Active Listening: Educators should practice active listening, demonstrating genuine interest in families’ concerns and perspectives. This approach fosters open dialogue and strengthens relationships (Rogers & Farson, 1987).

- Regular Updates: Providing families with regular updates on their child’s progress and school activities helps them feel involved and informed. Communication can take various forms, including newsletters, emails, and parent-teacher conferences.

- Cultural Sensitivity: Being aware of and sensitive to cultural differences in communication styles is crucial. For instance, some cultures may value indirect communication or non-verbal cues, which should be considered during interactions (Hofstede, 2001).

Active Listening Strategies

Active listening is a communication skill that involves fully concentrating, understanding, responding, and remembering what is being said. It requires more than just hearing words—it involves engaging with the speaker and showing genuine interest. Here are some key techniques to practice active listening effectively:

- Pay Full Attention: Give the speaker your undivided attention. Maintain eye contact, put away distractions (like your phone), and focus on their words, tone, and body language.

- Use Nonverbal Cues: Show that you are engaged through nodding, smiling, and maintaining an open posture. These signals encourage the speaker and show you are actively listening.

- Paraphrasing and Summarizing: Repeat or summarize key points in your own words to confirm understanding. For example, say, “So what you’re saying is…” or “It sounds like you mean…” This ensures clarity and reassures the speaker that their message is being received correctly.

- Ask Open-Ended Questions: Encourage deeper discussion by asking questions that require more than a yes/no answer. For example, “Can you tell me more about that?” or “How did that make you feel?”

- Reflecting Feelings: Acknowledge the speaker’s emotions to show empathy. Say things like, “It sounds like that was really frustrating for you.” This helps them feel understood and validated.

- Avoid Interrupting: Let the speaker finish their thoughts before responding. Interrupting can make them feel unheard or rushed.

- Provide Verbal Encouragement – Use short affirmations like “I see,” “That makes sense,” or “Go on” to keep the conversation flowing without taking over.

- Withhold Judgment: Listen with an open mind and avoid making assumptions. Even if you disagree, try to understand their perspective before responding.

- Respond Thoughtfully: After fully understanding the message, give a response that is relevant and considerate, ensuring the speaker feels valued.

- Follow Up: If the conversation involves an ongoing issue, check back later to show you care. A simple “How did that situation turn out?” reinforces your attentiveness.

Practicing active listening builds trust, strengthens relationships, and improves communication in both personal and professional settings. Would you like tips for a specific scenario, such as workplace communication or personal relationships?

Being Culturally Sensitive

Teachers can respect diversity by creating an inclusive, equitable, and culturally responsive learning environment where all students feel valued and supported. Here are some key ways teachers can achieve this:

- Acknowledge and Celebrate Differences: Recognizing students’ diverse backgrounds, cultures, languages, and experiences fosters a sense of belonging. Teachers can incorporate multicultural materials, celebrate cultural events, and encourage students to share their traditions.

- Use Inclusive Teaching Materials: Ensure that textbooks, examples, and classroom visuals represent different races, ethnicities, genders, abilities, and perspectives. Diverse literature, historical accounts, and case studies help all students see themselves reflected in learning.

- Encourage Open Discussions About Diversity: Create a classroom culture where students feel comfortable discussing their backgrounds, experiences, and perspectives. Promoting respectful conversations about different cultures, identities, and worldviews builds empathy and understanding.

- Adapt Teaching Methods to Different Learning Styles: Students learn in different ways, influenced by their cultural backgrounds and personal experiences. Using varied instructional strategies, uch as visual aids, group work, hands-on activities, and technology—ensures accessibility for all learners.

- Challenge Stereotypes and Bias: Address biases and misconceptions in the classroom by actively countering stereotypes in discussions and curriculum materials. Encouraging critical thinking about media portrayals, history, and current events helps students develop a more nuanced perspective.

- Foster a Safe and Inclusive Classroom Environment: Set clear expectations for respectful behavior and address discrimination or bullying immediately. A safe space allows students to express themselves without fear of judgment or exclusion.

- Use Culturally Responsive Teaching: Connect lessons to students’ backgrounds and lived experiences. This could involve incorporating culturally relevant examples, inviting guest speakers from diverse backgrounds, or integrating students’ home languages into classroom activities.

- Provide Equitable Opportunities for All Students: Recognize that some students face barriers to success due to socioeconomic status, disability, language barriers, or other factors. Offering additional support, differentiated instruction, and fair access to resources ensures that all students have equal opportunities to succeed.

- Model Respect and Inclusion: Teachers should lead by example by demonstrating respect for all cultures, backgrounds, and perspectives. This includes using inclusive language, respecting pronouns, and promoting collaboration among students from different backgrounds.

- Engage with Families and Communities: Building relationships with students’ families and communities fosters a more inclusive learning environment. Inviting parents to share cultural traditions, attending community events, and maintaining open communication help bridge cultural gaps.

By integrating these practices, teachers create a respectful, inclusive, and equitable learning environment where diversity is celebrated, and all students feel valued. Would you like specific strategies for a particular age group or subject?

Culturally Sensitive vs Insensitive Children’s Books

Children’s books play a crucial role in shaping young minds, and culturally insensitive images can reinforce stereotypes, misrepresent communities, and contribute to biases. Here’s what to consider when evaluating children’s books for cultural sensitivity and how to address problematic imagery:

Identifying Culturally Insensitive Images in Children’s Books

- Stereotypical Depictions: Some books portray racial, ethnic, or cultural groups through exaggerated or inaccurate features. For example, Indigenous people shown only in feathered headdresses or Asian characters with slanted eyes and rice hats reinforce harmful stereotypes.

- Lack of Diversity or Representation: Books that only feature one dominant race or culture while excluding others send a message that certain groups are less important or invisible.

- Tokenism: When characters from underrepresented groups are included only as background figures or without depth, it can feel like a superficial attempt at diversity rather than meaningful representation.

- Cultural Appropriation: When traditions, clothing, or symbols from a culture are used inaccurately or out of context, it can distort their meaning and show disrespect (e.g., depicting sacred Indigenous regalia as costumes).

- Negative or Inferior Portrayals: If a group is consistently depicted as primitive, unintelligent, or subservient, it reinforces harmful ideas. For example, historical books that only show enslaved people as passive without acknowledging their resistance and resilience create a one-sided narrative.

- Colonial or Racist Perspectives: Older books, in particular, may depict non-European cultures as “uncivilized” or reinforce a Eurocentric view of history. Books that glorify explorers while ignoring the harm done to Indigenous populations are common examples.

How to Address Culturally Insensitive Images

- Critically Evaluate Books Before Using Them: Teachers, parents, and librarians should assess books for biased images or narratives and choose materials that provide authentic and respectful representations of diverse cultures.

- Use Books as Learning Opportunities: Instead of outright banning books, discuss problematic elements with children in an age-appropriate way. Ask, “How do you think this picture makes people from that culture feel?” or “Why do you think the author chose to draw the character this way?”

- Choose Books by Diverse Authors and Illustrators: Seek out books written and illustrated by people from the cultures being represented. These books tend to be more accurate and respectful.

- Supplement with More Inclusive Books: If an older classic has valuable lessons but contains problematic images, pair it with a modern, inclusive book that presents a more balanced view.

- Advocate for Change in Publishing: Support and promote publishers committed to diversity and inclusion by choosing books that accurately reflect various cultural perspectives.

Examples of Culturally Insensitive vs. Inclusive Books

- Problematic: Dr. Seuss’s early books, which include racist caricatures of Asian, African, and Indigenous characters.

- Inclusive Alternative: Eyes That Kiss in the Corners by Joanna Ho, which celebrates Asian identity with affirming imagery.

- Problematic: Little House on the Prairie by Laura Ingalls Wilder, which contains negative depictions of Native Americans.

- Inclusive Alternative: We Are Water Protectors by Carole Lindstrom, an Indigenous-authored book about environmental activism.

By being mindful of culturally insensitive images in children’s books, adults can help foster respect, inclusion, and accurate representation in young readers. Educators and caregivers can play a vital role in connecting families with community resources that support their well-being and enhance children’s development. Access to resources can help families address various challenges, from financial instability to health concerns. It is an educator’s responsibility to help connect families with community resources

- Social Services: Programs that provide food assistance, housing support, and financial counseling can be invaluable for families facing economic hardship. Educators can help families navigate these services and ensure they receive the necessary support.

- Health Resources: Access to healthcare services, including mental health support, is crucial for families. Schools can partner with local health organizations to provide screenings, vaccinations, and wellness programs.

- Educational Resources: Community programs that offer tutoring, after-school activities, and enrichment opportunities can enhance children’s learning experiences. Educators should be familiar with these programs and actively promote them to families.

Conclusion

Families are a fundamental component of children’s development, influencing their social, emotional, and cognitive growth. By understanding and respecting diverse family structures, recognizing the impact of home environments, communicating effectively, and assisting families in accessing community resources, educators can create supportive networks that promote positive outcomes for all children.

References

- Amato, P. R. (2000). The impact of family structure on the educational attainment of children. Sociology of Education, 73(3), 202-224.

- Coleman, M., & Ganong, L. H. (2004). The role of stepfamily relationships in the adjustment of children of divorce. Family Relations, 53(1), 3-12.

- Cole, P. M., et al. (2004). Emotional regulation in children. In The Handbook of Child Psychology (Vol. 3). Wiley.

- Duncan, G. J., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (1997). Income effects across the generations. The Future of Children, 7(2), 40-54.

- Epstein, J. L. (2011). School, Family, and Community Partnerships: Preparing Educators and Improving Schools. Westview Press.

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations. SAGE Publications.

- Patterson, C. J. (2006). Children of lesbian and gay parents. The Future of Children, 16(2), 9-28.

- Rogers, C. R., & Farson, R. E. (1987). Active Listening. In Communications in Business Today. McGraw-Hill.

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2020). Demographic and Housing Characteristics. https://www.census.gov

Media Attributions

- Ecological_model © UNESCO is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license