6 Brain Development

The Science Behind our Thinking

Tanessa Sanchez and Kerry Diaz

Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter, you should be able to:

Brain development during the school-age years (approximately ages 5 to 12) plays a critical role in shaping how children think, learn, and interact with the world around them. This period is marked by significant growth in cognitive abilities, language development, emotional regulation, and social understanding. As children’s brains become more efficient and specialized, they begin to form deeper connections between experiences and knowledge, supporting more complex problem-solving and learning. Understanding how the brain develops during these formative years helps educators and caregivers create environments that promote curiosity, resilience, and academic success.

How the Brain Communicates

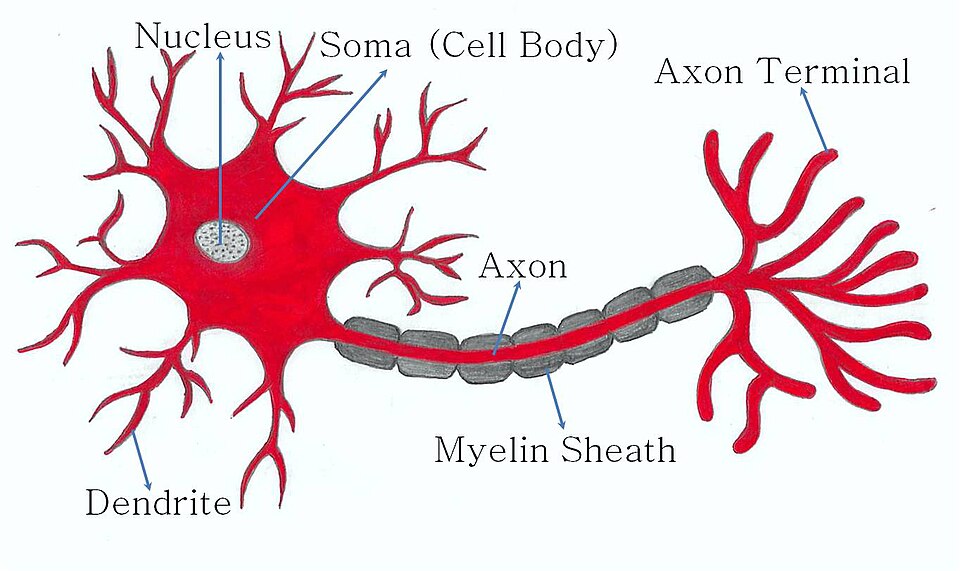

Neurons are the fundamental building blocks of the nervous system, responsible for transmitting information throughout the brain and body. They are specialized cells that communicate through electrical and chemical signals. A neuron consists of three main parts:

- Cell Body (Soma): Contains the nucleus, which holds genetic material and controls cell functions.

- Dendrites: Branch-like structures that receive signals from other neurons and send them to the cell body.

- Axon: A long fiber that transmits signals away from the cell body to other neurons, muscles, or glands. The axon is often covered in a myelin sheath, which speeds up signal transmission.

Neurons communicate with each other at junctions called synapses, where chemical messengers called neurotransmitters carry signals across the gap between neurons. This communication network is essential for everything the brain does, from thinking and learning to movement and emotions.

Brain Comparison: 3 & 6 Year Old

Brain of a 3-Year-Old

The brain of a 3-year-old and a 6-year-old differs significantly in structure, function, and efficiency due to rapid neural development. At age 3, the brain is highly plastic, meaning it is rapidly forming new neural connections. It has about twice as many synapses as an adult brain, allowing for incredible learning potential. However, these connections are not yet well-organized, making attention, impulse control, and memory less developed. The prefrontal cortex, which governs decision-making and self-regulation, is still immature, leading to impulsive behavior and difficulty managing emotions.

Brain of a 6-Year-Old

By age 6, the brain has begun synaptic pruning, a process that strengthens important neural pathways while eliminating unused ones. This makes thinking more efficient, improving problem-solving, attention span, and self-control. Myelination (the insulation of nerve fibers) continues, speeding up communication between brain regions, which helps with skills like reading, logical reasoning, and motor coordination. Additionally, the prefrontal cortex is more developed, allowing for better emotional regulation, longer attention spans, and improved social interactions.

Key Differences:

- Efficiency: A 6-year-old’s brain processes information more quickly due to synaptic pruning and myelination.

- Self-Regulation: Greater development in the prefrontal cortex allows for better impulse control and emotional management at age 6.

- Cognitive Abilities: A 6-year-old can engage in more complex thinking, problem-solving, and structured learning than a 3-year-old.

- Social Skills: Increased brain connectivity helps a 6-year-old understand social cues, cooperate with peers, and express emotions more effectively.

Overall, while a 3-year-old’s brain is highly adaptable and primed for learning, a 6-year-old’s brain is more refined, organized, and capable of handling more advanced cognitive and social tasks.

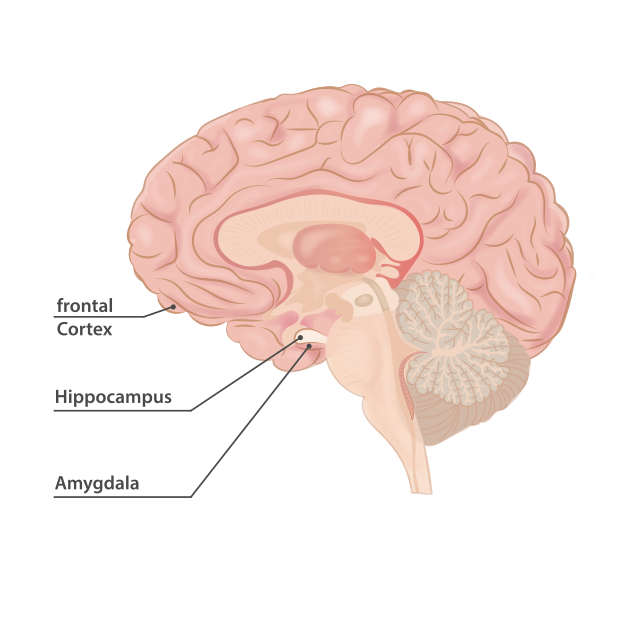

Between the ages of 4 and 6, the hippocampus, a brain structure critical for memory formation and learning, is undergoing significant development. This region, located deep in the brain’s temporal lobe, plays a key role in storing and organizing memories, spatial navigation, and connecting past experiences to new learning.

Key Developments in the Hippocampus (about age 6)

- Increased Synaptic Connections: The hippocampus continues to refine its neural networks, improving a child’s ability to store and retrieve long-term memories. This helps with learning new concepts, following multi-step instructions, and remembering past experiences in greater detail.

- Enhanced Myelination: Myelin, the protective coating around nerve fibers, continues to develop, allowing faster and more efficient communication between the hippocampus and other brain regions. This improves processing speed and memory consolidation.

- Improved Spatial Memory: The hippocampus is responsible for spatial awareness, helping children navigate their environment better, remember locations, and develop a stronger sense of direction.

- Integration with the Prefrontal Cortex: As the hippocampus matures, it works more closely with the prefrontal cortex, which helps children make connections between past experiences and new information, improving problem-solving and decision-making skills.

The frontal cortex, especially the prefrontal cortex, is undergoing rapid development, significantly influencing a child’s thinking, behavior, and emotional regulation. This brain region, located at the front of the brain, is responsible for higher-order functions such as attention, problem-solving, impulse control, and planning.

Key Developments in the Frontal Cortex (about age 6)

- Increased Synaptic Refinement: While the brain still has an abundance of neural connections, synaptic pruning begins, strengthening important pathways while eliminating unused ones. This makes cognitive processes more efficient, allowing for better focus and decision-making.

- Enhanced Myelination: Myelin, the fatty sheath that insulates nerve fibers, continues to develop, speeding up communication between brain regions. This improves a child’s ability to process information quickly and respond more thoughtfully rather than impulsively.

- Improved Executive Functioning: The prefrontal cortex is crucial for executive functions, which include:

- Attention Control: A 6-year-old can focus for longer periods, follow multi-step instructions, and filter out distractions better than a younger child.

- Impulse Regulation: They begin to show better self-control, resisting urges to act impulsively.

- Planning & Problem-Solving: They can anticipate consequences, make simple plans, and think more logically about solutions.

- Stronger Emotional Regulation: The maturing frontal cortex allows for better control of emotions. A 6-year-old can express frustration, excitement, or disappointment in more appropriate ways and begin to understand others’ emotions better.

- Greater Social Awareness: As connections between the frontal cortex and other brain regions (like the limbic system) strengthen, children develop a better sense of empathy, cooperation, and social rules.

Impact on a 6-Year-Old’s Abilities

- Better Focus in School: Improved attention span helps with tasks like reading, writing, and problem-solving.

- More Thoughtful Behavior: Children can follow rules more consistently and think before acting.

- Enhanced Emotional Control: They can manage emotions better, reducing tantrums and impulsive outbursts.

- Greater Independence: They can plan simple tasks, make decisions, and solve basic problems on their own.

While the frontal cortex is still far from fully developed (a process that continues into early adulthood), at age 6, children show noticeable improvements in thinking, behavior, and emotional regulation, preparing them for more structured learning and social interactions.

At age 6, the amygdala, a small almond-shaped structure deep in the brain, continues to develop and plays a crucial role in processing emotions, recognizing threats, and forming emotional memories. It is a key part of the limbic system, which helps regulate emotional responses and social interactions.

Key Developments in the Amygdala (about age 6)

- Increased Emotional Awareness: The amygdala is highly active in young children, helping them recognize and respond to emotions like happiness, fear, frustration, and excitement. By age 6, children become better at identifying emotions in themselves and others.

- Stronger Connections with the Prefrontal Cortex: The amygdala starts working more closely with the prefrontal cortex, which helps regulate emotional responses. This allows children to control impulsive reactions, express feelings in more appropriate ways, and recover more quickly from emotional upsets.

- Emotional Memory Formation: The amygdala plays a crucial role in forming and storing emotionally significant memories. At age 6, children are more likely to remember experiences that had a strong emotional impact, which influences how they perceive and react to similar situations in the future.

- Response to Stress and Fear: The amygdala still plays a dominant role in emotional reactions, meaning that fears, anxieties, and strong emotional responses can be intense. However, with increasing connections to the frontal cortex, children begin to develop better coping strategies for managing fear and stress.

Impact on a 6-Year-Old’s Abilities

- Improved Emotional Regulation: They start to express emotions more appropriately rather than through extreme reactions (though they may still struggle at times).

- Better Social Skills: Stronger amygdala-prefrontal cortex connections help with empathy, cooperation, and understanding others’ emotions.

- Developing Fear and Anxiety Responses: They begin to understand and articulate their fears (e.g., fear of the dark or new situations) while also learning strategies to manage them.

- Emotional Memory Influence: Past experiences shape how they react to similar events in the future, affecting their confidence, fears, and social behavior.

While the amygdala remains highly sensitive to emotions at this age, the increasing connections with the prefrontal cortex help children develop more balanced emotional responses and stronger social awareness.

Here’s a comparison chart showing the differences between the brains of a 3-year-old, 6-year-old, and 13-year-old, focusing on the hippocampus, frontal cortex, and amygdala:

| Brain Region | 3-Year-Old | 6-Year-Old | 13-Year-Old |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hippocampus (Memory & Learning) | Rapidly forming new connections but still developing long-term memory; mostly focused on simple recall and early learning. | Stronger memory formation and retrieval, better spatial awareness, improved ability to recall structured information. | More refined memory; can integrate past experiences into learning, understand abstract concepts, and recall details more accurately. |

| Frontal Cortex (Decision-Making & Self-Control) | Very immature; impulsive behavior, short attention span, minimal planning skills, and difficulty regulating emotions. | Improved impulse control, attention span, and problem-solving but still struggles with long-term planning and complex reasoning. | More developed reasoning, abstract thinking, and decision-making, but still struggles with impulse control and long-term planning due to ongoing maturation. |

| Amygdala (Emotions & Fear Response) | Dominates emotional reactions; intense fears, excitement, and frustration, with little ability to regulate feelings. | Strong emotional responses but beginning to regulate emotions better, especially with help from the developing frontal cortex. | Still highly active, leading to mood swings and strong emotions, often overriding rational thinking; heavily influenced by social interactions. |

Summary of Differences

- A 3-year-old’s brain is highly plastic, forming massive amounts of neural connections, but lacks refined memory, impulse control, and emotional regulation.

- A 6-year-old’s brain is becoming more structured, improving in memory, attention, and emotional control, but still developing advanced reasoning.

- A 13-year-old’s brain is more efficient and capable of deeper thinking, but the amygdala (emotion center) often overrides the prefrontal cortex, leading to impulsive decisions and emotional intensity.

Implications for Educators

Understanding how the brain develops at different stages of childhood is essential for creating effective, developmentally appropriate teaching strategies. The differences between the brain development of a 3-year-old, a 6-year-old, and a 13-year-old are substantial, and each stage presents unique needs and opportunities for learning. At age 3, the brain is undergoing rapid growth and forming millions of new neural connections. However, this age is also characterized by limited impulse control and short attention spans. Therefore, education for toddlers should prioritize play-based, hands-on experiences that engage the senses, foster social interaction, and support emerging language and emotional skills.

By age 6, the brain has begun the process of synaptic pruning, which strengthens frequently used connections and eliminates unused ones. This refinement enhances attention, memory, and the ability to process information. Children at this age are more ready for structured learning, but they still benefit greatly from multimodal instruction that includes storytelling, movement, visual supports, and interactive activities to reinforce learning and memory.

At age 13, children are in early adolescence, a stage marked by uneven brain development. While the prefrontal cortex—responsible for planning, impulse control, and critical thinking—is still maturing, the amygdala, which processes emotions, is highly active. This imbalance often results in increased emotional reactivity, social sensitivity, and a strong desire for peer acceptance. Middle school educators must therefore, balance academic challenges with support for emotional development, autonomy, and peer collaboration. Instruction should focus on real-world problem-solving, critical thinking, and opportunities for self-directed learning, while also providing guidance in emotional regulation and decision-making.

One specific area where brain development intersects with educational practice is Transitional Kindergarten (TK). For many 4- and young 5-year-olds, TK offers a bridge between preschool and traditional kindergarten, aligning well with the brain’s rapid growth in areas related to language, executive function, and emotional development. The hippocampus, a key structure involved in memory formation, is especially active during this stage, making TK an ideal time to introduce early literacy, numeracy, and social skills. However, it’s important to recognize the limitations of young children’s developing prefrontal cortex. Long periods of structured academic instruction may overwhelm them, especially if the curriculum is too rigid or not adapted to their developmental needs.

The most effective TK programs are those that balance structure with flexibility, incorporating hands-on exploration, movement, storytelling, peer play, and emotional learning. When aligned with current understanding of brain development, early childhood and elementary education becomes more inclusive, responsive, and effective. For educators, this means continually adapting teaching strategies to meet students where they are developmentally, supporting both their academic progress and their cognitive, social, and emotional growth.

Conclusion

Understanding brain development during childhood is essential for educators, caregivers, and parents seeking to support children’s learning, behavior, and emotional well-being. From ages 3 to 13, the brain undergoes remarkable changes—synaptic pruning, myelination, and the development of key regions such as the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, and amygdala. These changes influence how children think, feel, remember, and relate to others.At age 3, the brain is highly plastic, primed for learning but still immature in areas like impulse control and memory. By age 6, children begin to demonstrate improved executive function, self-regulation, and cognitive abilities due to strengthened neural connections. By age 13, the brain is capable of more abstract thought and deeper learning, though it is still influenced by emotional intensity as the prefrontal cortex continues to mature.

These developmental shifts underscore the importance of age-appropriate teaching strategies that align with neurological growth. Effective education supports not only academic skills but also social-emotional development, memory retention, and emotional regulation. Whether in Transitional Kindergarten, early elementary, or middle school, recognizing the connection between brain development and behavior enables educators to create supportive, responsive environments that foster whole-child development.

References

- Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. (2007). The Science of Early Childhood Development. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/the-science-of-early-childhood-development/

- Giedd, J. N. (2004). Structural magnetic resonance imaging of the adolescent brain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1021(1), 77–85.

- Jensen, E. (2005). Teaching with the Brain in Mind (2nd ed.). ASCD.

- National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. (2010). Early Experiences Can Alter Gene Expression and Affect Long-Term Development. Working Paper No. 10. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/wp10/

- Sousa, D. A. (2017). How the Brain Learns (5th ed.). Corwin Press.

- Thompson, R. A., & Nelson, C. A. (2001). Developmental science and the media: Early brain development. American Psychologist, 56(1), 5–15.

- Zelazo, P. D., & Carlson, S. M. (2012). Hot and cool executive function in childhood and adolescence: Development and plasticity. Child Development Perspectives, 6(4), 354–360.

Media Attributions

- Neuron_typical_structure © Ajimonthomas is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Brain_anatomy © InjuryMap, CC BY-SA 4.0 adapted by Wikimedia Commons is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license